On this day 73 years ago, French and American troops liberated Paris from Nazi occupation. Louise Dillery remembers; she was there.

Louise was born in Paris on December 14, 1925 to Radjzla (“Rose”) Silberstein and Israël Gradstein, Jewish Polish immigrants who met in Paris.

My mother was from Warsaw, and my father was from Lodz — I think it’s a big city in Poland. But they met in Paris and actually, the reason my mother went to Paris was because she was a favorite of her father. She was the prettiest and the smartest, and he had sent her to a school where she learned French; she spoke French perfectly, like a native. … She had step-sisters who were very jealous. So [when] her father died after a beating during a pogrom, you know a pogrom was when they had a little too much vodka and wanted to have fun they would say, “Let’s go get ourselves some Jews to beat up,” you know. And they beat up her father to the point that he died the next day. As soon as he died, then the stepsisters made her life a real hell, so she couldn’t stand to stay there. … So she came to Paris. And why my father came to Paris, I don’t know.

Louise knows little about her father’s childhood, except that he fled conscription into the Russian army when he was 14. Eventually he found his way to Paris and learned the trade of locksmith.

I wasn’t smart enough in those days to ask my father questions — and he was a very quiet, introverted man. Very, very kind, very good, but the little I know about him was through my mother. And I’m mad at myself that I didn’t know enough. Though I know from my mother that in those days Poland was occupied by Russia, and every so often the Russians would raid Jewish homes and take the boys as young as 14 into their armies, and the parents would never see them again. But always good people — you know there are always good people to help you — and they would warn the Jewish families, so the boys would just leave home. And that’s what my father did. That’s all I know; that he left home at the age of 14 for that reason. And where did he go before he landed in Paris? I don’t know. It’s a shame. But somewhere along the line he learned the trade of locksmith.

Israël established his own locksmith business in Paris and his little family enjoyed relative prosperity. But then the depression hit.

In Paris once they met and got married, he had his own little locksmith business. I guess it went pretty well — I mean, they were almost prosperous. I have pictures of my parents all dressed up as if everything’s great. And the great depression must have hit in Europe at the same time [as in the United States] — at least France, but if it hit France it must have affected everywhere — and so then that happened, and he lost his business, and he went to work in a factory where they made box springs that go under the mattress. That was very, very hard. In those days there were no unions, no protection; the workers that transport the box spring it’s heavy on their back. In no time at all he developed terrible callouses inside his hands. But he never complained, you know? And no matter what, he was always smiling and jolly and happy. Everybody loved him, and he loved everybody. And he had such a hard life.

As the family’s wealth declined, so did her mother’s health — and on June 15, 1939 Rose died of tuberculosis. It was the first time Louise saw her stoic father cry.

Israël Gradstein and Louise, dressed in mourning, February 1940

Less than a year later, on June 14, 1940, the German troops marched into Paris. Louise and her father were standing in front of Paris’ Hôtel de Ville (city hall) when the Nazis lowered the French flag and replaced it with a swastika. That was the second time Louise saw her father cry.

As Louise and her father turned to walk back to their apartment on the nearby Île St. Louis, they saw German soldiers with machine guns, ready to fire into the crowd at the first sign of trouble.

There was no trouble, though. “They’re so correct and polite,” Parisians would comment about the German soldiers. But gradually the city grew more desolate as those who were able fled into the countryside. Louise and her father didn’t know anyone outside of Paris, though, so they stayed. Food soon became scarce as rations and curfews were imposed.

When I talk about my life during the war, to give people an idea, if you think of a pork chop, that was one person per week — that was all their meat. If you think of butter, the little square you get in a restaurant, per person per week. Does that give you a little idea? That’s about all I can tell you. There was really severe rationing. There was a black market, you know. I had a neighbor upstairs who had an old jalopy, and he would go first thing on Monday morning and buy directly from the farmer different things — butter, eggs, you know — and then come home on Friday and sell for good money to people with the money on the black market. So some people didn’t suffer too much, and some did. That same neighbor upstairs — we had coupons for wine. I didn’t need wine, so I gave him my coupons for wine and he gave me his coupons for bread. And the bread was not the beautiful French bread, you know, it was kind of gray … I don’t know, when I look back, I ask, “How did we survive?” I don’t know.

Ultimately, it was because of the rations that Louise lost her father. She still remembers the date: November 25, 1942.

Israël — who had always been strong and stoic — was so sick that morning he literally could not get out of bed. Louise took his food-coupon book in addition to her own, and went to city hall to wait for the rations. She was so preoccupied that she didn’t notice two men watching her, until it was clear they were following her home. Without saying a word they barged through the apartment door.

[My father] had bad stomach ulcers. And in those days because there was no workmen’s compensation, there was no protection, you went to work whether you were hurting or not. So he was always stoic and strong. But that one day the ulcers were hurting him so badly that he literally could not get out of bed. And that was the day during the occupation that we had special books for coupons for food and everything, you know, rationing, but he couldn’t get out of bed. So I took his [coupon] book and mine and went to the mairie (city hall) — in fact it was the 25th of November. And I was waiting in line with those two books, and I was so preoccupied because I’d never seen my father in bed, sick or not sick. I thought he was dying; I was really, really scared so I did not notice there were two guys in civilian clothes who noticed I was holding two books. So I got the books and went home, and then realized I was being followed. And I panicked. I didn’t know where to go; if I had gone in the grocery store next door, they would have followed me. I felt trapped, so I just went home. They followed me. They walked right in. They saw him in bed, they made him get up, get dressed, and they took him.

For reasons she still doesn’t understand, the men left her behind.

I was there, like a statue. They didn’t take me. … So many times I’ve escaped death. It’s amazing; it makes me feel there’s a very special angel, or something protecting me. Because when they took my father from his sick bed I was right there, [and] in those days they took whole families. They could have taken me along with him, but they didn’t even look at me. That’s one of the mysteries of my life. I don’t know. Someday maybe I’ll know, but now I don’t know why. It’s just amazing. But it’s weird that they took him and I stood right there, and they made it to take whole families, but they didn’t even look at me.

After the liberation, Louise learned more about the men who took her father.

I found out after the liberation that those two guys in civilian clothes made it a point to arrest as many Jews as they could without orders. For a bonus. And fortunately, I found out — I was here [in Minnesota] already, though I was called once to the prefecture de police, to try to identify them, but all I could see was hats and overcoats; I could not recognize them. Anyway, finally they showed me that they were this height and all this against them. And finally they caught them and there was a trial, and they were executed by firing squad. And when I learned that, being here [in Minnesota] already, I was so happy. And I said once to a friend, “I don’t believe in vengeance, and yet I was so happy when I heard they were caught and later executed.” And my friend said, “That was not vengeance; that was justice.” So then, I don’t have to feel guilty anymore. Anyway, sometimes there’s justice in the world.

After the liberation, Louise also learned her father’s fate: He had died in a cattle car on the way to Auschwitz.

After the liberation there was this young man from the neighborhood who had been deported right with my father, and he came back — some did come back, you know — and he told me, “If it can be of any consolation to you, I can tell you that your father died right away.” Which means, you know they died standing up in the cattle cars on the trains, standing up like sardines. Most of them died on their way to Auschwitz. And because between his bad ulcers and the anguish of knowing that I was left behind that was enough to kill him. It’s of some consolation. He suffered a horrible agony but if it was quick … it’s a little bit of a consolation, you know. But there are a lot of stories like mine — I’m not unique at all.

The entrance to the building on the Île St. Louis where Louise and her father lived

The foyer of the apartment building where Louise and her father lived

Entrance to the apartment from which Israël Gradstein was taken

Louise was just 16, and all alone. But a Catholic priest from her neighborhood — Père Théomir Devaux — came to her aid, as did her friends. Louise would later learn that Père Devaux saved dozens of other Jewish children too.

Father Théomir Devaux, priest at Notre-Dame de Sion in Paris

That priest … I don’t know who told me to go see him. That was after my father was taken away. Not one of my friends remembers; it doesn’t matter. I went to see him, and he gave me money, and he told me to come the same day at the same hour same time, probably once a month I suppose, I don’t know. And he gave me money so I could pay the rent and stay in the apartment by myself. He probably gave me more than [I needed] for the rent. But I didn’t need much and my friend Ginette’s mother helped me, and my friends — people were rallying to me and helping, anyway. But that priest, he had … a beard, and real sad eyes. Père Devaux. In fact, I think my friend Nelly had a book and she found his picture. … He saved other people like me, but I was old enough to live on my own. Otherwise he would have found homes for young Jewish kids. He’s among the righteous in Jerusalem, or Tel Aviv, where they have a special place for the just, they call them. The righteous, you say in English.

In spite of the help from Père Devaux and her friends, daily life was still a struggle.

Of course, we choose to be on the side of good, or be on the side of evil, or be indifferent. When you’re indifferent maybe it’s almost like being on the side of bad. I don’t know. I’m not judging. There were people in France during the occupation who didn’t do anything wrong, but didn’t do anything to get involved and didn’t. [In] the building where I lived, they probably all knew right away that my father had been taken and they knew that I was all alone. But there wasn’t one who invited me to a meal, or something. They were just not caring enough, you know. And we heated our apartments with coal — and that was rationed too, like food — so when my father was living he was the one who went downstairs in the basement and filled the bucket, it was kind of tall and narrow, and he would bring it up three flights, with this pail of coal. So then I had to do that. And they saw me; they knew. I was only 16 and I had to go in the basement and I was kind of scrawny, you know, kind of underfed, and I had to drag … I was thinking of that just the other day. There wasn’t one [person] who offered to help me carry the pail.

Nevertheless, Louise continued attending classes at Lycée Victor Hugo (still located at 27, rue Sévigné) — in spite of a decree prohibiting Jewish children from attending school past the eighth grade. The school’s principal at the time, Madame Maugendre, gave Louise a scholarship for books, school supplies and lunch.

Louise, at far left in the second row, and her classmates at Lycée Victor Hugo 1942 – 1943

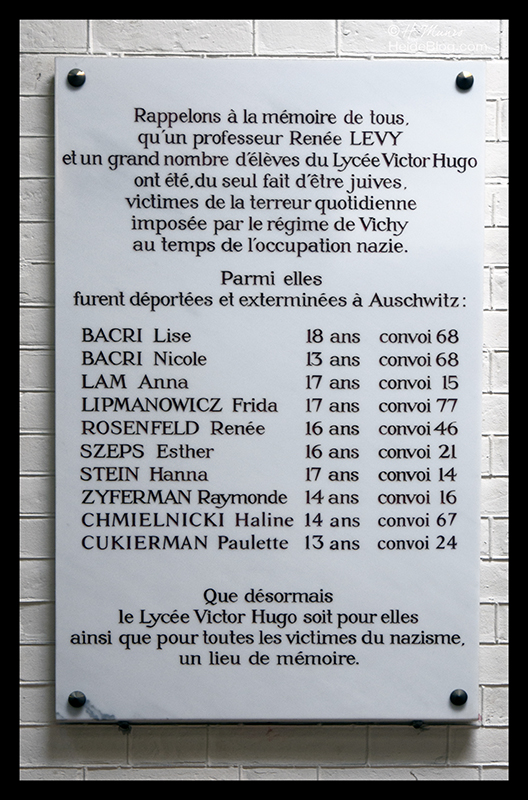

But not everyone was so lucky. Renée Lévy, a teacher at Louise’s high school, was arrested and later executed for being a member of the French resistance against the Nazis.

One of the many memorials inside the high school honors Renée Lévy

Louise also remembers her friend Esther Szeps simply not showing up for class one day. “We didn’t know about concentration camps in those days,” she said. Esther was among the 10 students from Lycée Victor Hugo who were murdered at Auschwitz.

As Paris became increasingly dangerous — especially for Jews — Louise sought shelter occasionally at her friends’ homes.

[At] my friend Ginette’s home, her mother bought on the black market for Sunday. So every Sunday she fixed a decent meal, and so I always ate there on Sunday. I always went there on Sunday and had a good meal.

It was also at Ginette’s home that Louise heard the first radio broadcasts about the Allies’ landing in Normandy on June 6.

We were … first of all, the landing was six of June. We heard about it in Paris; it was in Normandy — [and] Normandy is not far from Paris, as you know. So, nothing happened, so we thought it was false rumors. We didn’t believe it, and just tried to forget about it, you know. And then they must have been coming closer because even though it was not that far it was a real fierce struggle to get to Paris.

In the last week before the liberation there was fighting in the streets of Paris, so Louise stayed with Ginette’s family for safety.

But finally in the last week — and fortunately the last week I left home, my apartment, and I went to stay with my friend Ginette because I was always there. I felt safer there; her mother was so wonderful, and I had my pajamas and my toothbrush there. I was there more often than … and because that last week, there was a lot of fighting in the streets and people were killed — probably wounded too, I suppose. And I would not have been able to leave home and I don’t know what I would have done to eat. But anyway, I felt safer there.

On August 25 there was finally a breakthrough.

There was fighting in the street and everything, so I had the good sense to go there [to Ginette’s] and stay there. Their home was on Boulevard Voltaire, which you know is a big artery, and the windows faced the street so we could tell that the German convoys were going east real fast — they were leaving real fast. And then people started coming out with French flags and then I found out that [the Allies] were here, you know.

Louise and Ginette asked for permission to join the crowd that was gathering nearby at the Place de la République. They were at the base of the statue as the French Forces of the Interior rolled through, followed by American troops.

Ginette and I — well, we asked permission, you know, nice girls — we went, it wasn’t too far from the Place de la République, were the statue of the Republic is. And we got there in time to see the French Forces of the Interior, the FFI — I think Eisenhower saw to it that they were first to come in to liberate Paris. We were happy to see them, of course. And then we saw our Americans. Oh, oh my goodness … I tell you, they were gorgeous! I don’t care if you think I’m crazy, they were gorgeous, gorgeous, gorgeous!

Louise and Ginette were not yet out of danger, though.

And then there were snipers, German snipers, on the rooftops all around, you know, so they started shooting at us, and so we crouched at the foot of the lion [statue]. I didn’t realize but Ginette told me years, years later, I didn’t realize that people were killed and wounded. The snipers managed to do that. If I’d been killed, I would have died with a smile on my face.

Louise’s friends at the base of the statue where they took shelter from German sniper fire

After the war, Louise found work at a dental clinic in a U.S. Army hospital.

After the liberation, shortly after, I started working for an Army hospital, [in] the dental clinic. I was a secretary/receptionist. Those were happy years and I had my GIs. I was supposedly their guide, but I was more of a tourist than they were. Saw my first topless show. The greatest generation — they were real gentlemen. I ate with them — the GIs, not the officers. That was a big separation. Colonel Rodier became a father to me. He was a widower from New Jersey. My immediate boss was a sergeant, Bill Liedl.

It was also through her Army connections that she ended up in Minnesota.

[Bill Liedl] got me in touch with his family … his mother, she was a Soucheray. Joe Soucheray, I remember when he was born. They offered to sponsor me to come to this country. Since they sponsored me I came with a permanent visa. I figured I could stay for five years, earn a lot of money, travel … but I didn’t go back to Paris for 16 years. There is such a thing as destiny; it is written. And so they sponsored me. I’m grateful to them.

It was a tough adjustment at first.

I was thinking of going back [to Paris], but then a young woman neighbor who was working at [the College of] St. Catherine’s offered to take me [to the school]. She introduced me to Sister Mary Phillip, the head of the French department — she must have been highly respected because she took it upon herself to tell me that if I wanted to the following fall I could be a junior at St. Catherine’s for free. Even then it was expensive. And in exchange for that I could teach French classes. Another angel. She was an angel!

It was at the small college in St. Paul where she met John Dillery, the man who would become her husband. He too had come face-to-face with the Nazis, as an American GI in Belgium.

But before Louise and John could marry they would face one more trial.

As soon as I was back at St. Catherine’s I was in my element. That’s where I met my husband. I was doing student teaching; I wanted to teach French. But I had to have a clean bill of health, so they did an x-ray, and there I was: positive [for] TB (tuberculosis). My mother died of TB. And of course during the four years of occupation I was almost always hungry and didn’t have enough food. You can have the TB bacillus in you and never have TB if you’re not run-down. But I was run-down, so boom. I thought that was the end of everything. So I ended up being in the hospital for 19 months — a year as a strict bed-patient. [Laughs.] I can laugh [but] in those days — it was the old Ancker hospital on West 7th; it doesn’t exist anymore. The first year of strict bed-patient you had to use bedpans, you know. No bathroom. And in those days they didn’t even have curtains between the beds. Talk about intimacy! Everybody was very discreet. … Again, I was lucky, that’s when they discovered streptomycin, which took care of TB, but people still died though. There were two young women in the ward with me; I just loved those two. But they died of TB. For them it was too late. But then after a year of strict bed we could make our own bed and go to the bathroom. After that it wasn’t too long … so then at St. Catherine’s, just because I was discharged from the hospital, the doctors said don’t you dare get married, but I got married anyway. Don’t you dare have children. I had children! Because I’m old-fashioned, you know. [The doctor] said don’t nurse, and like a dummy I obeyed. He said, “You’ll be too tired,” so I didn’t nurse. But I had five kids. [The doctor] didn’t think I should get married right away so my husband and I waited a year. No fun, you know … we were ready. But after a year we got married. Wonderful, wonderful …

John died only 14 years after their wedding, at the age of 51.

We only had 14 years of marriage. He died during open-heart surgery. … He was full of energy, the life of the party. But then he ended up dying at 51. … You cannot ask why, because there is no answer. It is what it is, right? Life in general is not fair. We appreciate the good moments. I always say we should never take anything for granted.

In spite of everything, Louise still believes in the fundamental goodness of people.

I don’t care if people think I’m naïve, I really think there are more good people than bad. Because there are bastards who have caused so much suffering, but for one like that, so many more will come to the rescue and help. No matter what, no matter what the tragedy is in the news. When something tragic happens, right away if you see so many people, right? So I don’t think I’m crazy; I think there are really more good people than bad.

But that doesn’t mean that the bastards don’t do a lot of damage. But still … that’s why humanity has survived all those centuries, when you study history, it’s full of dark pages isn’t it. Tragedies, horrible things, wars — and yet humanity is still here. Must be that the good people were there.

And, in spite of everything, Louise still believes in God.

There was a great philosopher, a French philosopher named Pascal, who said, “We have nothing to lose and everything to gain by betting on the divine.” If you think about that saying, it’s quite profound. And why not? It doesn’t cost anything. If we assume and bet that there is a God, a higher force, a higher world, it doesn’t hurt. It doesn’t cost anything. You might as well bet on that.

Louise Gradstein Dillery

To learn more:

- The full transcript and recordings of my conversation with Louise will soon be archived at the Minnesota Historical Society.

- See Louise tell her story in this 2016 presentation.

- Hear her August 22, 2017 appearance on KFAI’s “Bonjour Minnesota.”

- Learn the fate of one of her classmates, Louise Pikovsky (in French).

This post is dedicated to the people who helped Louise — and to the hope that this chapter of history will never be repeated. My sincere thanks also to my friend Gilles Thomas in Paris for literally opening the door to Louise’s old high school and apartment building.

Thank you for making this valuable record available.

I was deeply honored that Louise allowed me to record it and share it, Michael — just as I’m honored and pleased you find it valuable. Thank you so much for stopping by, and for your kind comment.

Wow, such an inspiring story. It is sobering to think of the fear, desperation and tragedy that others have suffered that we in America have been able to avoid. How privileged you must have felt to hear her story firsthand.

“Privileged” is the perfect word to describe how I feel about knowing Louise, JP. You’re right also about the other privilege so many Americans have enjoyed, and therefore take for granted — and that is the privilege of having been spared this kind of hardship on US soil.

Please do not send anymore posts.. thanks

Sent from my iPad

>

Hello again Peter and Lynda,

I’m sorry you are receiving unwanted posts, but I can’t find you among my email subscribers — so I can’t cancel your subscription from my end. Please go to heideblog.com, scroll to the bottom of the page, and click the “Following” button. You should see a prompt to unsubscribe there; if you click on “Unfollow” I believe you’ll stop receiving future posts from this blog. Thank you!

Thank you Heide.

I got chills reading this! What an incredible woman and to be so positive and have such zest for life after all she has gone through is an example to us all. I love the last picture of Louise, her spark and personality shine through! Thank you so much for sharing her story! ❤

You are so sweet! Thank you for your kind words — I will pass them on to Louise, and I promise you they will make her smile even more brightly.

What an incredible story. To have been through so much and still have faith and in God and humanity is marvelous. Thanks for helping to share the story.

I agree with you 100%, Patti: It’s astounding — and also inspiring — that Louise was able to keep her faith in humanity after everything she endured. Thank you so much for stopping by … I will pass on your kind words!

Fantastic – truly – thank you for presenting Louise’s story. I love her belief in the goodness of people, her faith, and her resilience. All so beautiful, painful, terrifying, inspiring, and human. Human atrocities should never be repeated, yet they are, so reminders ongoing are crucial. Thank you for this post, and many gratitudes to Louise for sharing her story.

Thank you so much for your kind words, Lara … I will be sure to pass them on to Louise. I think it will mean the world to her that her story moved people as it did you.

Please do – tell her thank you. Human courage inspires everyone. It gives hope. Thank her for me :))) Give her my great regards and respect.

Beautifully said, Lara.

We do love Lara. 😉

Such a wonderfully information based post Heide. What persons of character. Thank you.

You’ve said it beautifully, Audrey: Louise is the very definition of character. And strength and humor, too. She is my role model in many ways!

We need these in our lives.

What a wonderful thing to have those stories written. I think you are doing a great job having the stories out… great job

Thank you very much for the encouragement, Björn. To paraphrase George Santayana, “Those who forget history are doomed to repeat it” — and this is one episode of history humanity must never forget or repeat. Thank you for stopping by!

A very well written documentation of Louise’s life in such terrible times. Such a terrible time.

As painful as it is to hear and remember these stories, we must keep them alive so future generations don’t have to re-live them. Thank you so much for stopping by, Sam, and for taking the time to comment.

What an incredible story, and yet as Louise says “not uncommon at all”. What an amazing experience to hear her story first hand and to visit her apartment and school. I would have sobbed and sobbed and sobbed. What a wretched time in history, yet so many survived, and helped others survive too. Louise is a shining light and so are you, HB. Thanks for sharing. I’m delighted to hear that your conversation will soon be archived.

Isn’t it sad to contemplate that Louise’s harrowing story is “not uncommon at all,” dear Alys? It’s impossible to imagine her an her father’s anguish and suffering, and to then multiply it by literally millions of human beings. But her hope and spirit really are a beacon to remind us of the tremendous capacity we humans have for survival, forgiveness, and even kindness amid such horror. Thank you so much for stopping by and for taking the time to leave your lovely comment.

What an amazing story. So moving and touching. Can’t even start to imagine how it must have been to live through WWII.

Thank you for your kind comment, Otto. I can’t begin to imagine what it was like to live through that dark period in our history either, and I count myself truly blessed for that.

Lost for words Heide, what a beautiful and moving story. Thank you.

I will pass your kind words on to Louise, Yann … mais en français. 😉 Thank you.

Avec plaisir. My next blog post will be for you. TTYS

How wonderful, Yann. Thank you in advance.

That’s a beautiful post, Heide. Thank you. Such a powerful life-story. So much misery and despair and yet also so much joy and hope. I can’t say “what a wonderful life”, and yet, as she says, she might have had a strong angel up there. But she’s also a pretty strong person. An inspiring article, thank you.

I’m pleased and honored that Louise’s story touched you so deeply, Pierre, and I will pass along your kind words to her. I agree with you wholeheartedly as well that although her guardian angel is strong, she is strong as well.

Beautiful one

Thank you so very much for sharing. I want to share this story of hope and faith with so many others! She is an incredible woman–and thankfully she has a great memory. So many would want to forget the details.

What I didn’t mention in my post is that Louise does have some amnesia because of the trauma, Roberta. There are a few stretches after her father was taken that she simply doesn’t remember. But as you say, what she does recall is a testament to her strength and resourcefulness. Thank you so much for stopping by!

Wow. Just wow. The strength of this generation and the people who survived never ceases to amaze and humble me. Just wow. Beautiful piece.

Isn’t Louise’s strength ASTOUNDING, Julie? And as she herself said, there were many others like her. I couldn’t help wondering whether many of us alive today could muster such mettle under similar circumstances. Let’s hope we never need to find out. Thank you so much for stopping by!

Thank you. This is something we should never, ever forget x

And thank YOU for reading, Sarah! x

That generation really was the greatest generation for so many reasons. Amazing story. Thank you for sharing it! Real life history is so much more moving than people think. Stories like this need to be shared. Thank you!!!

Such an informative piece by far Heide! Louise is seriously unbelievable. Thank you as always for sharing this amazing account laid in history 🙂

Thank YOU so much for reading Louise’s story, Sóla! You are right that she is an incredible woman, and it’s been a privilege to introduce her to my friends, if only virtually.

My pleasure and thank you again 🙂

Thank you for this one! Love the authenticity it is written with, and still so informative!

Thank you for stopping by, Julia, and especially for your kind words.

This interview that you’ve made is of great value! How good for Louise to have you as her attentive listener, how good for you to hear her life’s story, and how good for us to read it. Thank you!

Ellington

Thank you so much for your kind and thoughtful comment, Ellington. I’ll make sure Louise sees it.

Thank you, Heide. All credit to you for putting all this on the record. I think it is coming time to change the statement we read or hear every year on armistice day from ‘We will remember them’ to we must – should – remember them. …

I agree wholeheartedly! It’s reassuring to see how many individuals and organizations are rushing to preserve these stories before they’re lost. I feel immensely privileged to know Louise and to play some tiny role in recording and sharing her story. Thank you SO MUCH for taking the time to read it.

It was well worth it.

Hello dearest. I linked here from the bottom of your current post. What an honour it must have been to spend time with Louise and document her memories to share. That time in history, with so much darkness, yet she maintained hope and a sense of humour (saying if a German sniper had got her on Liberation day, she would have died with a smile on her face).

She had so much to overcome and not be taken, shot, starved or froze. I’m sad that none of her neighbours showed compassion but thank goodness some cared. I honestly don’t think we have the backbone to persevere today, what Louise did, as a 16 year old is amazing xK

I agree with you wholeheartedly that I’m not sure we’d have the backbone and mettle today that Louise did as a 16-year-old. Perhaps we would rise to the occasion, but thank goodness we haven’t (yet) been forced to find out. Thank you SO MUCH for reading Louise’s story so attentively, dear Kelly. It means the world to her that people care enough to listen. xx